How long is a cucumber? 🥒

Or: UTF-16 handling of astral planes and implications for JavaScript string indexing

tldr: 2.

String encoding in JavaScript is a bit weird. You might’ve heard this before. You might even have read about how, somewhat inexplicably, JavaScript does not use the almost universal UTF-8 file encoding but instead UTF-16 (see note 1). In this article I’m going to explore some of the more subtle and perplexing aspects of the weird way JavaScript encodes its strings, what this means for common operations like string indexing and go on to discuss how other languages handle the same problems.

So what’s all this Unicode stuff about then?

(If you’re already a Unicode wizard, go ahead and skip to the next section.)

Well, Unicode is a standard for defining characters like ‘F’, ‘♡’ or ‘🥒 ‘. (if you all you see is a blank box for this, just mentally replace it with another character like ☸). The way it does this is by giving each character a corresponding ‘‘code point’’ which is a numerical value like 135 (which happens to be this character: ‡). Usually, this numerical value is represented hexademically, meaning ‡ corresponds to code point 0x87.

The Unicode standard has a total of 1,114,112 code points, corresponding to 1,114,112 possible characters (the number of practically available characters is smaller than this, see note 2 for why this is). That’s a lot of characters! To split this up, this space is divided into 17 ‘‘planes’’, where each plane has 65,536 (or 216) code points. The first plane, which contains most of the commonly used characters like ‘‘9’’, ‘‘£’’, ‘‘ڞ’’ and ‘‘丧’’, is called the Basic Multilingual Plane (or BMP). This contains all of ASCII and extended ASCII; African, Middle-Eastern and non-Latin European scripts; Chinese, Japanese and Korean characters (collectively referred to as CJK characters); private use and what are known as ‘‘surrogate pairs’’. I’ll come onto what exactly surrogate pairs are used for a bit later.

Past this continent of common characters lies the vast, largely uninhabited and mysterious realms known as the 16 ‘‘astral planes’’ (or ‘‘supplementary planes’’, if you’re being boring).

The BMP takes up the first 216 code points in the range 0x0000 to 0xffff. This means that all BMP code points can be represented using only 16 bits or 2 bytes (some fewer). The astral planes, extending from 0x10000 to the full 0x10ffff, need between 3 and 4 bytes to represent them.

The 14th Century philosopher Nicole Oresmo demonstrates some astral plane characters. Images such as these would be distributed to the monks of the monasteries to aid their copying of Unicode manuscripts.

So what does this have to do with JavaScript and cucumbers?

Well, among the vast expanse of astral code points lies the cucumber, code point 0x1f952: 🥒 . Because the cucumber character is above the BMP, it needsmore than 16 bits to represent it. Yet, JavaScript uses UTF-16 which encodes each character using only 16 bits, so how does this work?!

The truth is that UTF-16 essentially uses two separate code points to represent this single character. This is where the ‘‘surrogate’’ code points that I mentioned earlier come in. Unicode reserves two blocks, the ‘‘High Surrogates’’: 0xd800 - 0xdbff and the ‘‘Low Surrogates’’: 0xdc00 - 0xdfff.

Each astral code point is represented in UTF-16 as one Low Surrogate and one High Surrogate by the following equation:

0x1000016 + (high_surrogate − 0xd80016) × 0x40016 + (low_surrogate − 0xdc0016)What this means is that, in JavaScript, the cucumber character 0x1f952 is represented as two separate codepoints: 55358 or 0xd83e (the high surrogate) and 56658 or 0xdd52 (the low surrogate).

Okay, so what does this mean for string indexing?

The astute reader may wonder what these surrogate pair representations of single characters means for the indexing of strings in JavaScript. When you have a string like var s = "hello there", you expect s[0] to give you the first character, s[3] to give you the fourth character and s[7] to give you the eight character. But what about the following code:

var cucumber = "🥒";

console.log(cucumber.length);

// -> 2So, even though it contains only a single character, JavaScript thinks that the cucumber string has a length of 2! We can delve a bit further:

var highSurrogate = cucumber[0];

var lowSurrogate = cucumber[1];

console.log(highSurrogate, highSurrogate.codePointAt());

// -> � 55358

console.log(lowSurrogate, lowSurrogate.codePointAt());

// -> � 56658What this shows is that string indexing works by assuming that all characters are within the BMP, and so are exactly 16 bits long. So the indexing picks out not the entire cucumber character, but only one of its two surrogate pairs!

This means that the string indexing works the same way as classical C-like array indexing, where s[4] just means getting the address of s and skipping forward 4 * sizeof s[0] bytes.

This maintains the O(1) speed of normal BMP string indexing, but is clearly bound to cause bugs when users are able to input astral characters into a script not expecting it! In fact, as I type out this article on http://dillinger.io, trying to remove an astral character with the ‘‘Delete’’ or ‘‘Backspace’’ buttons on a character like ‘‘😊’’ deletes not the character, but one of the surrogates, leaving the other surrogate as a weird question mark (�) which really confuses the cursor positioning…

It’s also a fun way to trick password forms into accepting fewer characters than they were asking for, like ‘‘😂😼😊✌️’’ which will trick JavaScript minimum character checks looking for a minimum of 8 characters. (This string does have a length of 8, but not quite for the reason you might think - see note X for why this is.)

The reason that this result is so counter-intuitive and unhelpful is that the underlying encoding used is not relevant to the programmer using Unicode strings. There’s two separate layers of abstraction here which are being muddled thanks to indexing (and by extension iteration) giving you the underlying Unicode implementation-specific codepoint instead of the value that the programmer actually wants (and probably expects…)!

What about this UTF-8 business then?

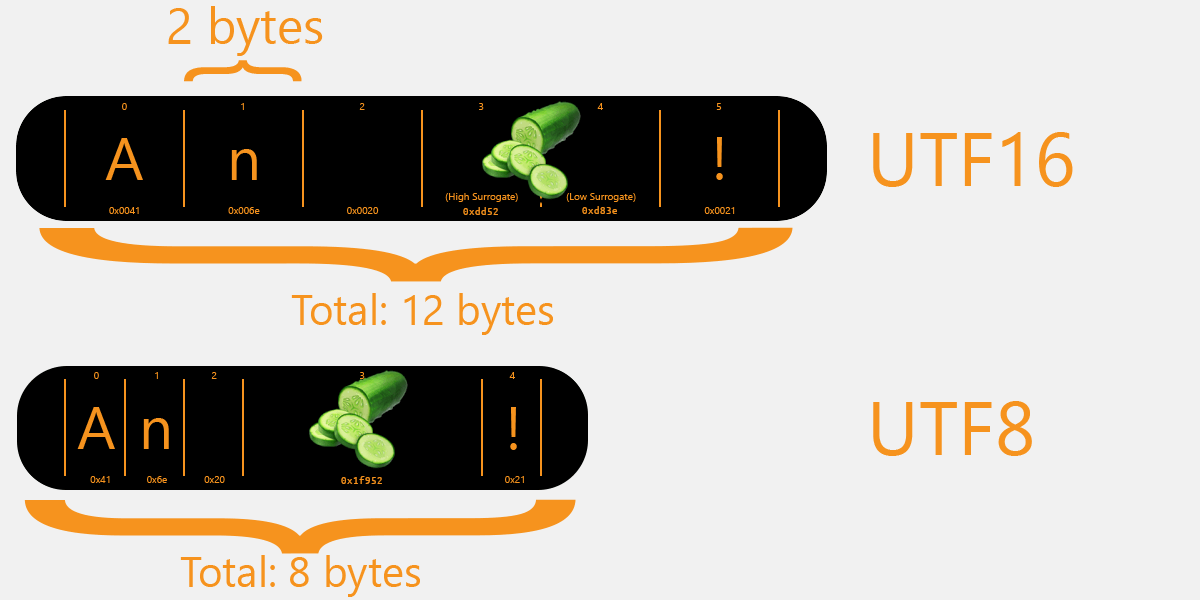

UTF-8 is a fully variable-length encoding, which means that there are no surrogate pairs necessary; ASCII character are only 1 byte long, but Arabic characters are 2 bytes long and the CJK characters are 3 bytes long. The astral code points extend from 3 to 4 bytes. UTF-16 is also not fixed size, but this is a more subtle point as it is only into the astral planes for the more obscure code points that multiple UTF-16 requires the variable length.

UTF-8 strings are always smaller (or same size as) UTF-16 or UTF-32 strings, which makes them the most compact Unicode encoding.

Another benefit of UTF-8 (and this applies to UTF-32 as well) is that because you don’t need to reserve a bunch of values for the surrogates we talked about earlier, you can actually include a bunch more actual characters. Unfortunately, as UTF-16 is so widely used those codepoints have to be reserved for surrogate use, even if it means they’re wasted in UTF-8 and UTF-32.

So how do other languages handle Unicode?

Well, JavaScript isn’t on its own:

- C - The standard types used are

charwhich is generally used as an 8-bit character for ASCII (and sometimes for other purposes whereuint8_tshould really be used instead) andwchar_t(introduced in C90) for handling any Unicode code point. In truth, the standard does not specify the size of eithercharorwchar_tSee note 3 for more information about this. - C++ - natively uses 8-bit

std::stringmuch like pure C. There isstd::wstringanalogous to C’swchar_twith correspondingstd::wcout,std::wcerr, etc. - Python - I’m not going to open this can of worms. To summarise, Python supports the full Unicode range via either UTF-16 (as per JavaScript) or UCS-4 which is where each character is 32-bits long and you don’t have to deal with any of this surrogate nonsense (although all your strings end of being much larger than they need to be). As per usual with Python, all of these details are handles under the hood without the programmer needing to know any of the details. There are differences relating to Python 2.x vs 3.x and compile-time flags and all this confusing mess, but you can happily code away without worrying about it.

- Java - Java’s

chartype is 16-bit length able to store the BMP characters only. TheStringtype uses UTF-16 to enable the full Unicode range as per JavaScript.

Then again, some of the newer languages seem to have seen the errors of the past and are adapting UTF-8 for strings natively:

- Go - Go source code is formatted as UTF-8. Strings are actually encoding-independent slices of bytes, however as Go source code is UTF-8 this practically means that almost all string literals are UTF-8. Indexing does not, however, index into the codepoints but the bytes. Bit weird, but there you go! See golang.org for more information on strings in Go.

- D - has standard library support for UTF-8, UTF-16 and UTF-32 via

string,wstringanddstringrespectively, so you’re spoilt for choice! - Rust - uses UTF-8 strings as standard - Rust source code is UTF-8, string literals are UTF-8, the

std::string::Stringencapsulates a UTF-8 string and primitive typestr(the borrowed counterpart tostd::string::String) is always valid UTF-8. Nice!

Check this link out for more information about how different programming languages handle Unicode.

Bonus round: UTF-8 string indexing in Rust

While languages like Go embrace UTF-8 but maintain indexing into bytes as the default, Rust goes even further in enforcing a UTF-8 treatment of all strings. So what happens when you try to index strings in Rust?

|

5 | println!("Normal[5]: '{}'", normal_string[5]);

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ `std::string::String` cannot be indexed by `{integer}`

|

= help: the trait `std::ops::Index<{integer}>` is not implemented for `std::string::String`In fact, Rust prevent indexing into strings using the normal [idx] syntax entirely on the basis that

a. It’s not clear whether indexing should work on bytes, code points or grapheme clusters.

b. Using the [idx] indexing syntax mentally implies O(1) execution, which won’t be the case for either code point or grapheme indexing.

Instead, Rust forces you to choose which to index into by providing two iterators:

my_string.bytes()for iterating over raw bytes - each item is given as au8.my_string.chars()for iterating over code points (technically it is for iterating over Unicode Scalar Values which is basically a Unicode code point excluding the low and high surrogates discussed earlier) - each item is given as achar, which is a 32-bit long representation of a single codepoint.

fn main() {

let normal_string = String::from("UTF-8! 🥒");

println!("Here's my normal UTF-8 string: '{}'", normal_string);

println!("\nHere's the chars iterator:");

println!("--------------------------");

for (i, c) in normal_string.chars().enumerate() {

println!("char at index {}: {}", i, c);

}

println!("\nHere's the bytes iterator:");

println!("--------------------------");

for (i, b) in normal_string.bytes().enumerate() {

println!("byte at index {}: {} ({})", i, b, char::from(b));

}

}

// Here's my normal UTF-8 string: 'UTF-8! 🥒'

//

// Here's the chars iterator:

// --------------------------

// char at index 0: U

// char at index 1: T

// char at index 2: F

// char at index 3: -

// char at index 4: 8

// char at index 5: !

// char at index 6:

// char at index 7: 🥒

//

// Here's the bytes iterator:

// --------------------------

// byte at index 0: 85 (U)

// byte at index 1: 84 (T)

// byte at index 2: 70 (F)

// byte at index 3: 45 (-)

// byte at index 4: 56 (8)

// byte at index 5: 33 (!)

// byte at index 6: 32 ( )

// byte at index 7: 240 (ð)

// byte at index 8: 159 ()

// byte at index 9: 165 (¥)

// byte at index 10: 146 ()You might notice that Rust doesn’t provide a standard library way of iterating through grapheme clusters, although there are crates that do exactly this. This might give you an idea of just how complicated this Unicode malarkey can get if you keep digging.

This means that Rust eschews the traditional string O(1) indexing. The pro of this is that you get out of it what you actually want, which is the nth visible rune instead of the nth byte or 16-bit char. The con is that we lose our O(1) speed string indexing as we now have to look through each previous character to check the length before we get to our rune at n, making lookup O(n).

A visualisation of how UTF-16 constructs strings compared to UTF-8. The resulting UTF-8 string is shorter, but indexing is not O(n) (as opposed to O(1)) due to the multi-byte nature of the UTF-8 character.

Aside: private use in Unicode

What do you see when you look at the following symbol: ‘’?

Some people will see a weird ‘p’-like symbol. On Linux, you might see a tiny Tux, the friendly Linux mascot:

That’s because it’s part of the “Private Use Areas” of the Unicode standard. This means that these codepoints, by definition, will never have any characters assigned to them by the Unicode Consortium.

Notes

Note 1

Technically, the ECMAScript 5 specification with which JavaScript is compliant specifies either UCS-2 or UTF-16 for string encoding, but we won’t delve into this too much here. For more information on this subtle distinction, go read this article, it’s a really interesting read and I’d very much recommend it if you enjoy reading this post.

Note 2

In fact, the actual number of characters is significantly smaller than this for a few reasons:

- 137,468 code points are for ‘‘private use’’, meaning they will by definition never be assigned values by the Unicode Consortium.

- 2,048 code points are used as ‘‘surrogates’’. I’ll discuss surrogates when it comes to UTF-16 in JavaScript later in this article.

- 66 code points are specified as non-characters and used internally by programs. For example, the assigned non-character

0xfffeis used by programs to check whether they’ve got the endianness of a text file right, because the endian complement to0xfffeis0xfeff, which is the Byte Order Mark (BOM). If a program encounters0xfffeat the start of a file, they it knows that they’ve got the endianess the wrong way around, because0xfffeis guaranteed not to be used by the file as a character.

This means that there are 1,111,998 possible characters, of which 974,530 characters are available for allocation.

As of Unicode 11.0 (released June 2018), there are 137,439 Unicode codepoints that have assigned values. This graph shows how the Unicode Consortium has assigned codepoints throughout its history:

As you can see, they’ve still got a lot of possible codepoints to choose from!

Note 3

In fact, the last symbol in that array - ✌️ - also known as “victory hand”, is within the BMP. So why does it appear as an emoji with length 2? Why, that’s an excellent question. To see what’s going on here, let’s break down how JavaScript sees the character:

const victory_hand = "✌️";

let i = 0;

for (const c of victory_hand) {

console.log("%d: %s U+%s", i, c, c.codePointAt(0).toString(16));

i++;

}

// Returns:

// 0: ✌ U+270c

// 1: ️ U+fe0fThe first character is the victory hand symbol U+270c (i.e. Unicode codepoint 0x270c) that we were expecting, but what is this second codepoint, the U+fe0f?

This U+fe0f codepoint is known as “variation selector-16” (i.e. the 16th codepoint within the “variation selector” range. What it does is tell the text rendering system to render the previous character not as a black-and-white normal text character but as a colourful graphical character - the emoji that we actually see.

In the parlance of Unicode, the BMP victory hand and the variation selector-16 together form a “grapheme cluster”, meaning that both codepoints together form the graphical character seen on screen.

This presentation - “Unicode: Good, Bad and Ugly” - has a really thorough explanation of graphemes and the different complications around them, along with how they’re handled in various languages.

Note 4

C90 defines wchar_t as “an integral type whose range of values can represent distinct codes for all members of the largest extended character set specified among the supported locales” (ISO 9899:1990 §4.1.5).

This is a classic example of C specifications not really giving away enough details to really nail down an API, which is one of the reasons that undefined behaviour is so easy to accidentally stumble upon in C. Classic examples of under-defined standards in C is that char need not be 8 bits long, int not needing to be 16 bits long, double not needing to be 4 bytes - all of these are left up to the compiler to implement.

Updates and Corrections

2018-12-27 - Several points updated, rephrased and explanations clarified followed some interesting comments on Lobsters.

- The number of code points in a simple Unicode plane is 65,536 not 65,535 as stated previously (thanks to /u/Nayuki for pointing this mistake out).

- Explanation of Rust indexing was updated to clarify that both byte-indexing and codepoint-indexing is possible, but neither using the native indexing syntax (thanks to /u/Nayuki and /u/Kyrias for clarifying this).

- CJK characters are in the 3-byte range in UTF-8, not the 2-byte range as previously stated (thanks to /u/Nayuki for pointing this mistake out).

- The C standard is far more vague than I initially understood in defining

charandwchar_t. Post updated to reflect this (thanks to /u/tedu and /u/notriddle for explaining this). - Added graph depicting assignment of codepoints by the Unicode Consortium.

- Lots of minor rephrasing and refactoring.

2018-12-30 - Minor correction, additional explanation and note.

- Added note on victory hand emoji and grapheme clusters (thanks to Lars Dieckow for explaining this, and for providing the code snippet and link included in the added note).

- The cucumber emoji is represented as two separate codepoints, not two separate characters as previously stated (thanks to Lars Dieckow for pointing this mistake out).

- Added additional note complaining about why string indexing giving UTF-16 codepoints is unhelpful.